I’m interviewing James Ellroy over lunch in half an hour and I realize I have already miscalculated. We’re meeting at Gallagher’s Steak House in Mid-Town, New York and I have decided to walk from my apartment on the Upper West Side to clear my head and think of some really interesting questions that he hasn’t been asked a million times before. It is however already 80 degrees Fahrenheit with a humidity level that makes it feel much warmer. I’m wearing my bog standard black jeans with black DM’s, a suicidal sartorial choice for a Belfast boy. Back home in Northern Ireland people start fainting and complaining about the heat when it gets into the low 60’s.

Born and bred in Los Angeles and a famous writer for over two decades, I imagine Ellroy is used to all kinds of heat. Used also to interviewers showing up flustered, sweaty and maybe a little bit panicky. Ellroy’s reputation precedes him. There are numerous reported incidents of him not suffering fools gladly. There was that time when he heckled a documentary about his own life at the premier and he has abruptly terminated interviews for tardiness or because the interviewer was poorly prepared.

As it happens I arrive at Gallagher’s Steak House on West 52nd Street before Ellroy. I get a quiet table in the corner and order a Moscow Mule (vodka, lime juice, ginger & ginger beer) as a restorative. It hits the spot, and as I’m searching for my list of questions, Ellroy comes in looking lean and tall and hungry. He’s 71 years old and casually dressed but he looks younger and sharper, and if you didn’t know, you’d peg him as a philosophy professor, perhaps in his early sixties.

“Hey Adrian, good to meet you,” he says, shaking my hand. “I gotta hit the can.”

“Can I order you a drink in the meantime?”

“Just black coffee,” he says.

Ellroy doesn’t drink anymore, having had substance abuse and alcohol problems in his teens and twenties. His parents both were drinkers. Alcohol destabilized their marriage and in his memoir My Dark Places and in other essays he describes his mother’s rages and melancholy promiscuity when under the influence. Her still-unsolved rape and murder when he was ten years old was, of course, a critical turning point in young James’s life.

Back from the bathroom, Ellroy scans the menu and orders a dozen clams and a salad he makes up himself. I settle for the safer bet of a club sandwich.

“So what about you. They say you’re from Belfast, is that right?” he asks.

“Yes that is right.”

“I’m just back from the UK and Ireland. You know, I think I prefer Belfast to Dublin. Something about the people, something about the vibe,” he says and smiles.

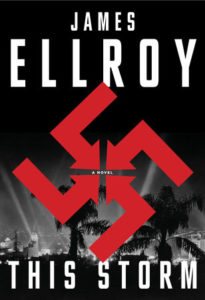

I know he’s not kissing up. He never kisses up. If there’s one thing that Ellroy is famous for telling, it’s for telling it straight. “I read the review you wrote of This Storm in The Guardian. I never read reviews but they gave it to me when I was there so I had to read it.”

“And?”

“Well you actually read the book so that’s something. You wouldn’t believe how many people come to interview me or who review my stuff and they only read the first 100 pages, you can tell. It’s lazy and unprofessional. I liked the thing you said in the review about David Peace. He’s good.”

This takes me aback. The night before I’d been trawling through other Ellroy interviews where he talks about never reading any contemporaries with a few exceptions for spy fiction authors such as Daniel Silva and John le Carré. “What do you like about Peace?” I ask him.

“I like his world. His Yorkshire reminds me of my Los Angeles.”

“Have you ever read his football novels?” I ask hopefully, but Ellroy shakes his head. The image in my mind of James Ellroy in his lair reading about Brian Clough and Bill Shankly and Emlyn Hughes is too delicious to let go. “They’re excellent. The Damned United is a minor masterpiece and Red or Dead is a major masterpiece.”

“I wanted the scale of those Red Riding books to be bigger. I wanted deeper. Like Winslow does in The Cartel. I wanted more from Peace. And as for soccer, I don’t know. The only sport I know about is boxing,” he says.

This opens the floodgates and for the next twenty minutes we talk about the state of the sport, particularly the heavyweight division. He knows one of Deontay Wilder’s trainers and likes him. I tell him about Tyson Fury’s Belfast connections. We agree that the Wilder-Fury was one for the ages. We discuss the recent Joshua-Ruiz fight which he missed because he was in England. He thinks Joshua is too nice to be a fighter but I counter with how charming I found Ruiz to be on The Jimmy Kimmel Show. Ellroy has no TV in his apartment so I’m not sure if he knows who Jimmy Kimmel is. He has no TV, no cell phone, no internet, no computer. He writes in long hand and sends the pages to be typed. He corrects the typed pages in long hand.

“How do you watch the fights if you have no TV? Do you go to a bar?”

Ellroy explains that his girlfriend (his ex-wife) lives in the same apartment building as him in Denver, Colorado. She has a TV, radio and computer. We talk a little bit about Denver. He moved there a little over three years ago; I lived there from 1999 – 2008. I talk about the Beats and their surprising connections to the city but his eyes are glazing over and I can tell Ellroy couldn’t care less about the Beats. I ask him about Kerouac, Burroughs et. al. and he confirms that he doesn’t rate them as writers or as people. “Immoral and self centered and dull,” he says.

He asks me what I thought of Denver.

“It was nice. I liked the snow. I grew up in Ireland where we never really got snow. I taught at this private school, there where they got Fridays off to ski. I never skied before so they sent me for lessons so I could supervise the kids. So what do you do in Denver for fun?”

He tells me he enjoys driving or walking around downtown. He describes a monastic lifestyle of writing in the morning, exercising on an elliptical machine, more writing and then down time with his girlfriend reading or listening to music.

“What music?” I ask.

“The good stuff. Beethoven, Bruckner, Mahler, Mozart.”

“I noticed in This Storm there’s a subplot about the smuggling of Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony into America.”

“Ah so you did read the book all the way through.”

We talk This Storm for a while. I suggest that Roosevelt’s internment of the Japanese is the moral disaster at the heart of the book which he sort of agrees with. I then ask him why he felt the need to kill two of my favorite characters in the novel.

“It was their time.”

“You let Dudley Smith live to a ripe old age, but you kill these two. Come on man, it’s not fair.”

“And that’s the point isn’t it? To give you a picture of an unfair, immoral, corrupt world.”

We talk some more about POV characters and their arcs and how important it is for him to understand even the vilest of men. “Liberals hate that about my books,” he says.

And yet I wonder if maybe he’s a kind of secret liberal, delving deep into fascist demimonde exposing the underside of America, a project the late Roberto Bolaño was doing in his last fictions. Ellroy is not interested in such conjecturing. He avoids politics and he confirms to me what he said at the Hay Festival, that he’ll never write a book that takes place any later than 1972.

We get to talking about American Tabloid and I ask him about Don DeLillo and he lights up. “Libra changed my life!” Did he ever tell DeLillo that? He says that they talked briefly in Amsterdam at a literary festival.

WE GET TO TALKING ABOUT AMERICAN TABLOID AND I ASK HIM ABOUT DON DELILLO AND HE LIGHTS UP. “LIBRACHANGED MY LIFE!”

I tentatively discuss class in American fiction. He worked full time as a golf caddy until his fifth book and I ask him if American letters is perhaps too full of rich kids who graduate from expensive MFA programs with an elegant prose style and nothing much to say. He grunts an agreement but clearly to him this is airy-fairy theorizing and he’s not really into it.

The conversation moves onto film. He talks about his love of the actor Paddy Considine and I excitedly tell him about The Ferryman on Broadway. “They have a live goose on stage!” I say as my closing argument and he laughs, but tells me he’s leaving New York tonight.

We unpack our favorite and least favorite movies. He tells me he is not a fan of Tarantino or most modern movies. He hates The Wire. Somehow we find ourselves in a heated argument about, of all things, Billy Wilder. Ellroy can’t stand him. “Not even Some Like It Hot?” Ellroy shakes his head. He explains that he thinks the way Marilyn Monroe was portrayed was sordid and unbecoming.

“OUR REAL FAMILY NAME WASN’T ELLROY BUT MCILROY BUT MY GRANDFATHER CHANGED IT BECAUSE HE DIDN’T WANT TO BE ASSOCIATED WITH THE SHANTY IRISH. MY DAD TOO WAS ALWAYS SAYING THAT IF I MISBEHAVED HE’D SEND ME TO THE CATHOLIC CHRISTIAN BROTHERS SCHOOL.”

It’s Martin Scorsese who really rubs him the wrong way. He doesn’t like movies that glamorize or fetishize drug taking, alcoholism or revel in violence for the sake of violence. I wonder if this is a reaction to his childhood or a Puritan streak. We get to talking about religion and he tells me he’s a Lutheran but on his father’s side they were Irish Presbyterian. This hasn’t come up before in my previous research and I’m a little surprised by it. I dig deeper. “Our real family name wasn’t Ellroy but McIlroy but my grandfather changed it because he didn’t want to be associated with the Shanty Irish. My dad too was always saying that if I misbehaved he’d send me to the Catholic Christian Brothers School.”

“The McIlroys were from Ulster. No wonder you like Belfast. It’s an atavistic thing,” I tell him laughing. He’s laughing too now and warms to the theme. “Joyce aside all the great Irish writers were Protestant,” he says. “Beckett, Wilde, Shaw, Synge, not O’Casey. . .”

“Nope O’Casey too, despite the name. But not Behan or Heaney or Muldoon or. . .”

He looks at his watch. We’ve been talking for over two hours.

“Oh I’m sorry I lost track of time,” I say.

He brushes it off. “We’ll talk again, I enjoyed this,” he says.

I look at my list of questions that I was going to ask. I haven’t gotten to any of them. I wanted to know what poetry he reads. There’s an Anne Sexton epigraph in one of his books and I’m a huge fan of her writing. . . It will have to keep.

We shake hands.

His charming publicist arrives and picks up the tab and Ellroy leaves a tip that makes the waiter catch his breath for a moment.

This morning he was with The New York Times. For lunch it was me and now Ellroy’s off to do another interview. He seems to dig all this. To me he’s a classic introvert/extrovert who hibernates for four years between books before enjoying this carnival of publicity and performance.

I fold up my question sheet. I didn’t get to ask him about race or Donald Trump or a clever critical review of This Storm I’d just read in The New Statesman. Next time, I tell myself, I’m going to steer us clear of the boxing.